Can our expectations about how full a food will make us influence how full we actually get? The idea seems plausible enough. There are many known cases of mind-over-matter. One well-known case is the use of placebos. Placebos are given during studies to subjects who believe they are actually taking medication, and they often experience relief of symptoms from whatever is being studied, even though they are taking a sugar pill.

Can our expectations about how full a food will make us influence how full we actually get? The idea seems plausible enough. There are many known cases of mind-over-matter. One well-known case is the use of placebos. Placebos are given during studies to subjects who believe they are actually taking medication, and they often experience relief of symptoms from whatever is being studied, even though they are taking a sugar pill.

When we expect events to be a certain way, they often turn out that way. If we go to a party in a bad mood and expect the party to be bad, what will happen? The party will most likely be bad. If we went to that same party expecting to have a good time, you would be more likely to enjoy it. Or take the case of people who think they have some kind of illness and imagine symptoms, although there is nothing actually wrong with them. I can go on and on, but I think the point is made. Research suggests that how full we expect to get strongly influences how full we get. Satiety is the condition of being full after eating food.

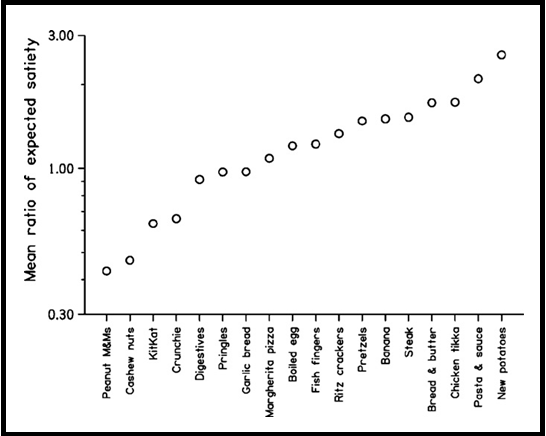

Satiety Ratings of Various Foods

One study showed subjects pictures of various foods and asked them to rate how full they believed eating those foods would make them feel (1). They compared the expected satiety of each food versus the amount of calories and also compared the expected satiety of different foods that had the same calories (1). When comparing the satiety of pasta with sauce to fish fingers, subjects believed that 200 kcal of pasta with sauce would deliver the same satiety as 345 kcal of fish fingers (1). This means subjects believed fish fingers were not very filling and would tend to eat more calories than they realized. They believed pasta was more filling and would tend not to eat more pasta than they realized.

The second part of the experiment tested the expected satiety of 18 different foods (1). The results are as follows:

Generally speaking, this chart shows that people tend to associate fats with low satiety and carbohydrates with higher satiety. It was found that people expected 200 kcal of pasta and sauce to fill them up as much as 894 kcal of cashews (1). The problem occurs when people’s expectations of satiety from a food vary markedly depending on the calorie content of that food. In simpler terms, people overeat foods that they believe are not filling and that happen to be high in calories, which can increase their daily caloric intake significantly.

You must consciously tell yourself that something like nuts is very high in calories and tends to not be that filling, so you should measure out a certain intake, or if you have a hard time controlling your intake of something like nuts, you should avoid them. If we don’t expect a food to be filling, we may not get filled and overeat it. This can also affect the portion sizes we order in a restaurant or take at a buffet.

The study found that besides our expectations of fats not filling us up, we also did not expect energy-dense foods in general not to fill us up. Many snacks are energy-dense, and this assumption could be dangerous over time. Another reason is that we may never eat these snack foods to the point where we are full, so we logically expect them not to fill us in the future.

Another study had subjects choose their meals based on expected satiation, volume, and the energy content of meals (4). They found that foods of equal volume were not found to be equally satiating (4). Together, expected satiation and perceived volume of the food explained a majority of how people chose their ideal portions (4). Expected satiation of food was an excellent predictor of portion selection (4). Subjects rated their decision about the satiety of food as “effortless,” which means they likely do not sit there and consciously analyze the volume and energy density of the food but instead rely on past experience and instincts (4).

Comparing Meals and Snacks

A study found that subjects who received a “snack” became less full than those who ate a “meal,” although both the snack and the meal contained the same amount of calories (9). Snack foods are generally believed not to be very satiating, while foods considered meals are believed to be much more satiating. Although the meal and snack had the same calories, subjects ate less following the meal and more following the snack (9). When the same foods were used but presented in different ways, consumption of food was reduced for subjects believing they ate a meal compared to subjects who believed they ate a snack (120 versus 223 calories) (9). Our expectations of how well a food should fill us obviously caused the difference in satiety when comparing the snack foods to the meals when they had the same calories.

A study found that subjects ate 35% more cookies when they were labeled as healthy or unhealthy. Labeling foods as “diet,” “low-calorie,” and the like may cause people to believe that these products will not be very filling, which can lead to overconsumption. It may be wiser to label foods as “filling,” “hunger-reducing,” or “satisfying.”

How the Weight of a Container Influences How Full Do We Expect to Get?

A study investigated whether the weight of the container that food is served in influences expected satiety and fullness (7). The researchers put identical amounts of yogurt in a light or heavy bowl (7). Subjects reported that they expected the yogurt in the heavier container to be more satiating than the yogurt in the less heavy container (7). When subjects were holding the heavy and less heavy containers, they were shown pictures of foods on a screen and asked how much of the shown food they would have to consume to keep off hunger to the same extent as the yogurt in whichever bowl they were holding (7). When holding the heavier bowl, the subjects indicated they would have to consume significantly more pasta, salted crackers, peanut butter cookies, and grapes to fill them up, the same as the yogurt in the heavier bowl, compared to the amount they needed when holding the less heavy bowl (7).

Since the subjects believed they needed more food to get as full as the yogurt in the heavier container, they showed that they believed the yogurt in the heavier container contained more calories than in the less heavy container (7). The weight of the container was also shown to influence the perceived density of the sample (7). On average, the yogurt in the heavier bowl was rated as denser than the yogurt in the less heavy bowl (7). This study showed that the weight of the container can influence the expected satiety of the food inside before even tasting it (7).

How Expected Portion Size Influences Fullness

Another study assigned subjects into two different groups. One group was shown a “large portion” of fruit that they believed was going to be in their smoothie, and the other group was shown a “small portion” of fruit that they believed would be in their smoothie (8). The researchers wanted to measure how the expected portion of fruit would influence satiety. After looking at the picture, subjects were presented with their smoothie. Subjects assessed the expected satiety of the smoothie and gave appetite ratings before and three hours after eating the smoothie (8). Both smoothies contained the same amount of calories.

The subjects believed that the large portion would deliver 41% more satiety than the smaller portion (8). After lunch, participants in the small portion group had higher ratings of hunger and lower ratings of fullness than the large portion group (8). The differences in hunger and satiety lasted during the whole 3-hour post-lunch period (8). Although both smoothies contained the same amount of fruit, the large portion group believed they were getting more fruit than the other group and also experienced greater reductions in hunger than the small portion group (8).

Discussion

The authors of the previous study believed that expected satiety may have an effect on actual physiological mechanisms, such as causing the release of a regulatory peptide or influencing gastric emptying (8). Cognitive beliefs about food and the expected satiety may cause changes in chemicals in the brain that further influence chemicals in our stomach and intestines, which regulate hunger.

Most of you have probably heard about a Russian physiologist from the early 1900s named Ivan Pavlov. Pavlov fed dogs each time a bell rang, and eventually the dogs salivated just from the sound of the bell, believing they would get food. Their brains became conditioned and associated the ringing of the bell with the consumption of food, and just hearing the bell was enough to influence the physiology, which increased salivation in expectation of a meal.

Is it such a stretch to imagine our brain being conditioned to the sight and expected satiety of a food from past experiences that it sets in motion the release of various hormones and chemicals associated with the expected satiety from that food? Research does support the idea that past experiences with food and how much they filled us up influence how full we think we will get when we eat those foods again. It is a learned response. An evolutionary shortcut to deciding whether or not a certain food is worth our resources and energy to obtain. For hunter-gatherers, knowing which foods had a lot of calories was the difference between life and death, so remembering which foods were filling and which weren’t was paramount for their survival.

Expected satiety can have a major impact on what foods we buy and consume. Overeating high-calorie foods that we do not expect to fill us (such as soda and nuts) can cause significant weight gain over time. Soup is one food item that gives more satiety than would be expected from its calorie content. This could be because soup is thought of as a meal and not a snack. Numerous studies have shown that consuming low-sodium soup is a healthy and effective way to keep off hunger and reduce your caloric intake at meals consumed after the soup. Having a salad before a meal has the same effect.

Be careful when eating snacks. Consciously remember that snacks can contain significant amounts of calories and do not typically fill us up, so choose healthier snacks that can reduce hunger, like fresh vegetables, and less processed foods, like granola bars, that do little to reduce hunger! If you notice a snack does not fill you up at all, try to find one that will. Eating a “snack” that does not fill you up and does not have any or little nutrients is a waste of your precious calories.

Sources

- Brunstrom, J. M., Shakeshaft, N. G., & Scott-Samuel, N. E. (2008). Measuring ‘expected satiety’in a range of common foods using a method of constant stimuli. Appetite, 51(3), 604-614.

- Brunstrom, J. M., Collingwood, J., & Rogers, P. J. (2010). Perceived volume, expected satiation, and the energy content of self-selected meals. Appetite, 55(1), 25-29.

- Capaldi, E. D., Owens, J. Q., & Privitera, G. J. (2006). Isocaloric meal and snack foods differentially affect eating behavior. Appetite, 46(2), 117-123.

- Piqueras-Fiszman, B., & Spence, C. (2012). The weight of the container influences expected satiety, perceived density, and subsequent expected fullness. Appetite, 58(2), 559-562.

- Brunstrom, J. M., Brown, S., Hinton, E. C., Rogers, P. J., & Fay, S. H. (2011). ‘Expected satiety’changes hunger and fullness in the inter-meal interval. Appetite, 56(2), 310-315.

Your mind can play a big role in how you feel. Reading this article is an example of how your mind can determine your satiety.

I want to share with you how when I was a kid my mind made me sick. LOL! When I was a little girl my family planned a vacation trip and we had to take a boat ride for about 30 minutes to reach our destination. I told them I didn’t want to go because I didn’t want to take the boat ride. (I was feeling scare of the ocean); the trip was still on and I got sick with fever and vomits. My parents took me to the doctor and they did some tests and nothing was wrong with my health. At the end, my family had to cancel the trip and a few days later I was healthy again. So our mind can be very powerful!

For a happy ending to my story, a few years later my parents planned the same trip again and I ended up in the boat ride and had a great time on my vacation. We traveled to the same place a few times after that one. And I have so many nice and happy memories of my trips there! So glad I went!

Your example of Pavlov is so interesting it reminded me when I took a psychology class in college and I read about it in my text book. It is fascinating how the dogs reacted to the whistle thinking they were going to be fed.

Hey Lucia. I am glad you ended up enjoying your vacation! Our mind is capable of making us sad, happy, scared, hungry, etc. This is part of the reason that meditation is so important in learning to control your thoughts a bit better. Also being consciously aware of how many calories you are eating is important as some foods that we do not expect to fill us up actually have a lot of calories and remembering this will help prevent you from overeating. We must learn to rely more on the objective caloric properties of food and not just how full we get in order to keep caloric intake to a minimum. Thanks for commenting!