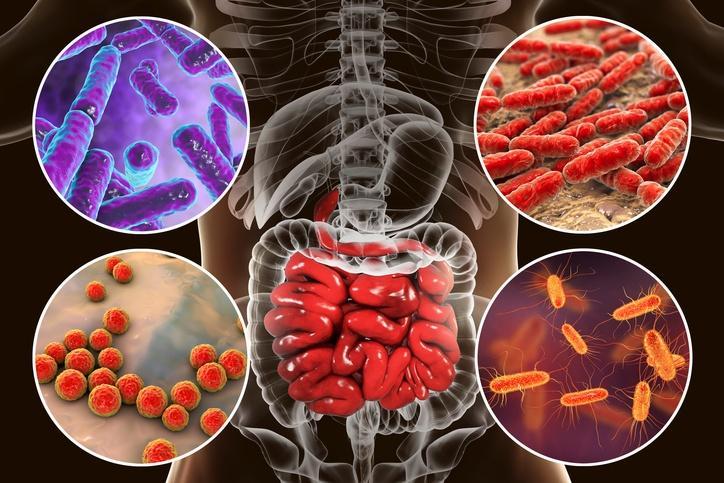

Believe it or not, we share our body with billions of itty-bitty bacteria. In fact, these microscopic bacteria make up 1–3% of our total body mass! Bacteria inhabit all areas of our body, including our mouth, skin, organs, and vagina. Each area of the body has its own unique inhabitants, with the human gut containing 500–1,000 different bacterial species. While we have yet to discover the function of the vast majority of the bacteria, we do know that some help regulate our immune system. Bacteria in our gut help us break down carbohydrates that we normally would be unable to digest, such as fiber.

For a healthy person, our bacteria rarely cause illness. If someone happens to have a compromised immune system, opportunistic bacteria that are normally harmless can cause sickness. Each person has not only different types of bacteria but also differing amounts. Science is just starting to explore the role of gut microbiota (the microbe population living in our intestines), and there is even speculation that it may influence obesity, but I am not yet sold on this. Our gut bacteria have evolved alongside human evolution. We feed them, and they provide necessary and important functions (like vitamin production) we could not otherwise get.

Unfortunately, most of the press about bacteria involves disease-causing bacteria. I guess that makes for more frightening and compelling news stories. This blog will discuss the role of gut bacteria and also talk about how antibiotics can seriously alter our natural gut flora (I will use gut flora and gut microbiota interchangeably throughout this blog). Throughout this blog, I will refer to our gut bacteria as our commensal bacteria.

Negative side effects of antibiotic use

While antibiotics can be lifesavers, I believe that we currently overuse them. I will not go over this point since I already discussed it in my blog, Creation of the Superbug: how bacteria are outsmarting antibiotics and the long-term repercussions. When we take antibiotics, we not only kill the bad bacteria but also the good bacteria. Antibiotics are indiscriminate killers of bacteria. Many people develop side effects from antibiotic use, at least partly because we kill our natural bacteria that fend off disease. The most obvious symptom is antibiotic-associated diarrhea caused by the overgrowth of Clostridium difficile and the subsequent development of pseudomembranous colitis (inflammation of the colon) that can result in death (1).

The incidence of antibiotic-associated diarrhea depends on the class of antibiotic used. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea occurs in 10–25% of those treated with amoxicillin clavulante, 5–10% of those treated with ampicillin, and 15-20% of those given cefixime (2). Causes of this diarrhea range from a serious illness called colitis to “nuisance diarrhea” with no other symptoms.

Antibiotic-associated colitis from a C. difficile infection

- difficile infection almost always follows the use of antibiotics (3). Symptoms of antibiotic-associated colitis are fever, abdominal cramping, leukocytosis (a high white blood cell count—an inflammatory reaction usually from an infection) and changes on endoscopic inspection of the biopsy (2). Infection with C. difficile only accounts for 10–20% of the cases of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. It does, however, account for nearly all the cases of colitis associated with antibiotic therapy (2). Other possible causes of antibiotic-associated diarrhea include infection from another type of pathogen, through the effect that the antibiotics have directly on the intestinal mucosa, and metabolic consequences from the reduced concentrations of fecal flora (2).

Decreased microbiota diversity is seen in those with C. difficile infection. When antibiotic treatment is discontinued in C. difficile mice, the recovery of their normal microbiota leads to almost total eradication of C. difficile from the GI tract (3). C. difficile usually occurs in hospital or long-term care patients and is almost always associated with antibiotic use (4). The incidence of this disease has skyrocketed in recent years, from less than 150,000 cases in 2000 to 500,000 cases in 2006, with about 15,000–20,000 deaths (4). C. difficile produces two toxins in the colon that destroy the integrity of the mucosal barrier, leading to Clostridium difficile colitis.

Clostridium difficile colitis can mimic flu-like symptoms and release toxins that cause blotting and diarrhea with abdominal pain, which can be severe. It is also possible to die from extreme inflammation of the colon. If someone has a Clostridium difficile infection, stopping the antibiotics is often enough to resolve the infection. More serious cases require more antibiotics. Relapses occur in about 20% of cases. Clostridium difficile infection kills about 14,000 people a year in the United States.

Antibiotic associated Candida overgrowth

A friend of mine took antibiotics for a bacterial infection and ended up with oral thrush as a result of subsequent fungal overgrowth following antibiotic use. It turns out that this is a common side effect of antibiotic use. Candida albicans is a yeast found in small amounts throughout the body. When people take antibiotics, candida albicans takes advantage of the destruction of our microbiota and grows rapidly in different parts of the body, sometimes in the mouth, called thrush, and sometimes in the genital area, called a yeast infection. The friend I previously mentioned developed candida albicans overgrowth of his mouth, which produced a nasty-looking white tongue. He was given antifungal medication to kill the overgrowth. He said the medication tasted horrible!

An Australian study measured rates of Candida infection in women before and after antibiotic use (5). Before antibiotic use, Candida species were found in 21% of the women, and after antibiotic use, Candida species were found in 37% of the women. The primary species found was Candida albicans (73%), followed by Candida glabrata (20%). Yeast infection is so common in women following antibiotic use that it may actually affect antibiotic compliance in women.

Healthy adults rarely get thrush. It is very common in patients who have a compromised immune system such as in those with AIDS, people getting chemotherapy and people taking antibiotics. This shows killing of the intestinal bacteria has effects on other non bacterial organisms such as yeast. More evidence of this was shown from a study which found decreased bacterial count in feces of those taking antibiotics but an increase in the candida albicans count in the feces compared to controls who were not taking antibiotics (6). There are also other candida species that are opportunistic. A 2005 study found that previous antibiotic use was associated with hospital-acquired Candida glabrata and Candida krusei (7).

Destroying our good bacteria produces a chain reaction, giving any opportunistic bacteria, yeast, or virus the chance to multiply and take up the space where our commensal bacteria usually reside. It also lends credence to the idea that the good bacteria that occupy our gut are necessary to suppress the overgrowth of dangerous organisms. While thrush certainly looks gross, it can become more than a nuisance if it enters your bloodstream.

Relapse of the original infection

Another serious consequence of antibiotic use is the reoccurrence of the original infection, or relapse, which occurs in 20–25% of cases (2). Relapse is marked by the reemergence of symptoms, usually occurring 3–21 days after the antibiotic is discontinued. Most relapses are resolved by taking another course of antibiotics, usually lasting 10 days, although 3–5% of patients have more than six relapses. Treating a reoccurrence of C. difficile can be long and expensive, and it is treated with other drugs for 4-6 weeks while the normal flora of our gut returns.

How does our microbiota protect us?

Our natural microbiota protects us from incoming disease-causing bacteria in many ways, including by competing for space with incoming bacteria, competing for similar nutrients with bad bacteria, and inhibiting them through the release of inhibitory molecules (1). Essentially, if our good bacteria take up most of the space in our tissues, there will be no room for incoming disease-causing bacteria. We want our helpful bacteria to multiply and thrive. This is what normally happens. Antibiotic use changes that.

The bacterial make-up of the colon is so different between each person that even twins share less than 50% of their species-level bacterial taxa (8). Despite the interpersonal variety in the colon bacterial communities, science has discovered that they all share a similar core of functions (8).

How our microbiota inhibits pathogens

Byproducts of anerobic (without oxygen) bacteria metabolism, such as short-chain fatty acids and acetate, inhibit the growth of certain pathogens like Salmonella (4). Studies have shown that different strains of gut bacteria provide protection against enterotoxigenic (bacteria that attack the intestines) E. coli infection (4).

How our microbiota inhibits Candida overgrowth

There is a thick layer of mucus in our gut that is naturally produced by our microflora. This layer prevents yeast from adhering to the intestinal wall. This mucus also produces inhibitory substances like short-chain fatty acids (made from the fermentation of carbohydrates by the intestinal bacteria) and secondary bile acids that prevent yeast from growing. The last factor preventing candida albicans overgrowth is that our natural flora competes with it for nutrients. These are the reasons that the destruction of our natural microflora by antibiotics allows candida albicans to spread rapidly.

Impact of antibiotics on our microbiota

After antibiotic use, there is usually a decrease in the diversity of our microbiota, although it usually returns to normal in the following days or weeks (1). Well, maybe it does not return to exactly how it was before the antibiotic use. While most of our innate bacteria return, some are lost forever. Researchers found a decreased count of certain gut bacteria after administration of antibiotics, a change that persisted up to two years after antibiotic discontinuation (9).

Our commensal bacteria function as a community. Some bacteria require the byproducts of other bacteria for nutrients, while others require other bacteria to remove their waste. Because of this, antibiotics that kill one type of bacteria may indirectly kill another type whose survival depends on the killed bacteria (2).

One study showed that treatment with an antibiotic did not affect the total bacterial amount in the small intestine but almost completely wiped out the lactobacilli bacteria. Destroying specific bacteria can upset the delicate balance of our gut microflora. Another study found that alteration in the gut microbiota by antibiotic use led to allergic disorders by affecting the development of basophils (a type of white blood cell—our immune system cells) (10). Also found were that changes in our gut flora caused by antibiotics led to an increase in serum IgE levels, leading to an increase in the frequency and number of basophils in the blood.

A study compared the fecal bacterial makeup of subjects before and after antibiotic use (11). Bacterial diversity decreased after antibiotic use as the core microbiota fell from 29 to 12 taxa and the most dominant genus of bacteria shifted (11). Also shown was that microbial abundance and composition were affected by antibiotic use, along with microbial diversity.

Rebuilding our gut flora following antibiotic use

As our commensal community of bacteria rebuilds following the use of antibiotics, there is a reduced resistance to the colonization of the gut by new foreign bacteria, which can cause disease and replace our helpful bacteria (12). With repeated antibiotic use, our natural gut flora continues to change and paves the way for the multiplication of bacteria that have developed resistance to antibiotics, thereby displacing our normal flora.

Studies have shown that antibiotics that kill anaerobic bacteria result in significant increases in vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) (a certain type of bacteria that is resistant to the antibiotic vancomycin) in human fecal samples (4). VRE can take over the whole intestinal lumen in humans, representing 99% of the bacterial flora (4). Although not as dangerous as C. difficile, VRE can accumulate to the point where it causes a VRE bloodstream infection (4). Besides this infection, VRE colonization results in a lack of microflora diversity, which can have negative effects on our immune system and leave us more susceptible to disease.

Discussion

Keep in mind that we are only observing changes in our microbiota that produce measurable illness. There is likely more damage from destroying our microbiota, but we cannot measure it as it produces no visible illness. We have no idea what the majority of the bacteria in our colon do. This type of research is in its infancy. I am sure the more we learn about the effects of antibiotics on our natural bacteria, the more we will learn about the damage they have on our immune system.

Between the findings from this blog and the possibility of developing antibiotic-resistant bacteria, I would only take antibiotics if I had an illness that could possibly kill me. Our microbiota did not evolve to handle the detrimental effects of antibiotics. In nature, nothing wipes out both good and bad bacteria like antibiotics do. I tend to air on the side of caution, and I believe that we should restrict the use of antibiotics for serious cases that actually require their use and not illnesses we can just wait a week to recover from. We are only discovering the observable adverse effects of antibiotics, such as diarrhea and thrush.

With scientists knowing so little about the composition of our gut bacteria, how can we trust them to know that our intestinal bacteria go back to normal in the weeks following antibiotic use? It seems rather daunting to compare the millions of bacteria in our gut before and after antibiotic use. Our gut bacteria have been shaped from birth through adulthood. When wiping out our commensal bacteria with antibiotics, I am skeptical that everything just goes back to normal in a few months, especially since opportunistic and antibiotic-resistant bacteria multiply and displace our commensal bacteria during and following our antibiotic use.

Next time your doctor wants to prescribe you antibiotics, make sure you ask him if they are really necessary. You can also ask for antibiotics that target specific bacteria instead of antibiotics that target all classes of bacteria. If you need antibiotics, there has been research showing that taking probiotics along with antibiotics may offset some of the side effects of antibiotic use. Research dealing with the beneficial effects of probiotics on our gut flora during antibiotic use is so interesting that I will write a blog about it in the coming months!

Sources

1) Willing, B. P., Russell, S. L., & Finlay, B. B. (2011). Shifting the balance: antibiotic effects on host–microbiota mutualism. Nature Reviews Microbiology,9(4), 233-243.

2) Bartlett, J. G. (2002). Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. New England journal of medicine, 346(5), 334-339.

3) Ubeda, C., & Pamer, E. G. (2012). Antibiotics, microbiota, and immune defense. Trends in immunology, 33(9), 459-466.

4) Littman, D. R., & Pamer, E. G. (2011). Role of the commensal microbiota in normal and pathogenic host immune responses. Cell host & microbe, 10(4), 311-323.

5) Pirotta, M. V., & Garland, S. M. (2006). Genital Candida species detected in samples from women in Melbourne, Australia, before and after treatment with antibiotics. Journal of clinical microbiology, 44(9), 3213-3217.

6) Krause, R., & Reisinger, E. C. (2005). Candida and antibiotic‐associated diarrhoea. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 11(1), 1-2.

7) Lin, M. Y., Carmeli, Y., Zumsteg, J., Flores, E. L., Tolentino, J., Sreeramoju, P., & Weber, S. G. (2005). Prior antimicrobial therapy and risk for hospital-acquired Candida glabrata and Candida krusei fungemia: a case-case-control study. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 49(11), 4555-4560.

8) Turnbaugh, P. J., Quince, C., Faith, J. J., McHardy, A. C., Yatsunenko, T., Niazi, F., … & Gordon, J. I. (2010). Organismal, genetic, and transcriptional variation in the deeply sequenced gut microbiomes of identical twins.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(16), 7503-7508.

9) Jernberg, C., Löfmark, S., Edlund, C., & Jansson, J. K. (2007). Long-term ecological impacts of antibiotic administration on the human intestinal microbiota. The ISME journal, 1(1), 56-66.

10) Russell, S. L., Gold, M. J., Hartmann, M., Willing, B. P., Thorson, L., Wlodarska, M., … & Finlay, B. B. (2012). Early life antibiotic‐driven changes in microbiota enhance susceptibility to allergic asthma. EMBO reports, 13(5), 440-447.

11) Panda, S., Casellas, F., Vivancos, J. L., Cors, M. G., Santiago, A., Cuenca, S., … & Manichanh, C. (2014). Short-Term Effect of Antibiotics on Human Gut Microbiota. PloS one, 9(4), e95476.

12) Clemente, J. C., Ursell, L. K., Parfrey, L. W., & Knight, R. (2012). The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell, 148(6), 1258-1270.

ESTE TEMA ME ENCANTO YA QUE HACE SAVER QUE EL ANTIBIOTICO MATA LA FLORA INTESTINAL

AHORA QUISIERA SAVER COMO HACER PARA RECUPERAR LA FLORA INTESTINAL CON ALGUN

PRODUCTO NATURAL…

Hey Rita. Yo recomendaria comprar probioticos para salvando tu flora intestinal cuando toma el antibiotico. Tomando los probioticos con los antibioticos puede te ayudar mucho!! Los probioticos ayudara con los efectos secundarios de los antibioticos como nausea, diarrea y evitara el crecimiento de los bacterias malas en su colon. Tengo un buen probiotico pero no se si tu puedes comprarlo en Guatemala…

Hello Rob:

Please I would like to know what we need to eat to help our bacteria…Also, Lucia’s mom is asking what natural product she can use to fix the guts.

HUgo

Hey Hugo. Our diet has a big impact on our gut bacteria. I would recommend eating plant products for fiber which help with beneficial gut bacteria. Some probiotics can be helpful too although the studies are mixed. I will email you a probiotic I recently bought that I recommend. I will also do a blog on the effect of food on our gut bacteria in the coming weeks

If you analyze how many things have bacteria you would be living with anxiety all the time. It is scary how we are surrounded by bacteria. I think you have to be very careful what you eat and where you eat to avoid bacteria intake because even if you are careful you can be consuming bad bacteria from eating a meal at a restaurant etc. Like I mentioned as a comment in one of your following blogs, I do take a probiotic every morning to maintain my good bacteria.