From personal experience, most can attest to being cranky or out of it after a night of short sleep. Some people, myself included, feel the same way if they sleep too long. Research has confirmed a U-shaped type of association between sleep length and disease risk. Both short and long sleep increase the risk of various diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. You can read about the association between sleep length and disease risk in my previous blog. This blog will focus solely on the association between sleep length and all-cause mortality and will expand upon the previous blog I have written on the relationship between sleep and disease risk.

From personal experience, most can attest to being cranky or out of it after a night of short sleep. Some people, myself included, feel the same way if they sleep too long. Research has confirmed a U-shaped type of association between sleep length and disease risk. Both short and long sleep increase the risk of various diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. You can read about the association between sleep length and disease risk in my previous blog. This blog will focus solely on the association between sleep length and all-cause mortality and will expand upon the previous blog I have written on the relationship between sleep and disease risk.

What is all-cause mortality?

All-cause mortality does not look at one specific cause of death. All-cause mortality is the number of deaths from any cause in a certain population. For this blog, all-cause mortality would be the number of deaths in a population being studied and its relation to sleep length. If more people died in the short sleep group than in the long sleep group, the all-cause mortality would be higher in that population for short sleep for that time period.

Sleep duration and mortality risk follows a U-shaped curve

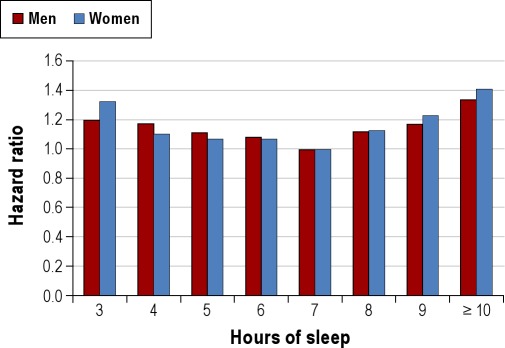

There appears to be an optimal amount of sleep that is associated with a reduced risk of all-cause mortality. As you can see in the image below, that amount appears to be about 7 hours a night. As you start getting less than 7 hours or more than 7 hours, you can see the hazard ratio (higher hazard of death) increasing.

What happens to people that stop sleeping?

Scientists know exactly how long people can go without sleep before dying. People with fatal familial insomnia (FFI) are never able to progress past the shallow stage of Stage 1 sleep. Once the disease sets in, the survival rate of individuals ranges from seven to thirty-six months. Early and late symptoms of the disease include insomnia, panic attacks, hallucinations, dementia, coma, and finally death (2). Luckily, this disease is fairly rare, only affecting about 100 people worldwide.

Sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality

A 2007 study followed the sleep patterns of participants between 1985–88 (Phase 1) and then again in 1991–93 (Phase 3) and looked at the relationship between sleep duration and all-cause mortality (3). Those who slept for 5–6 hours at baseline (Phase 1) but increased their sleep time later on (Phase 3) showed a lowered mortality risk compared to those who slept 5–6 hours a night at both Phase 1 and Phase 3. Participants whose sleep fell below 7 hours or above 8 hours were at an increased risk of mortality. Subjects who increased their sleep from 6 hours a night to 7 hours experienced a decreased mortality risk, while those that increased from 6 hours to 8 hours saw no reduction in mortality risk.

When researchers examined the Nurse’s Health Study (121,000 nurses), they found that both short and long sleep durations led to an increased risk of mortality (4). There was a 15% increase in mortality risk for women sleeping 5 hours a night, compared to 7 hours a night. Women sleeping more than 9 hours saw a 42% increase in mortality risk compared to those sleeping 7 hours.

An older study of 6900 adults in California found that the lowest death rates were found in those sleeping 7-8 hours a night (5). Men that slept less than 6 hours a night or more than 9 hours a night saw 1.7 times the total death rate compared to men that slept 7 or 8 hours a night, which amounted to a 70% higher death rate over a 9-year period.

Lastly, a study of 1.1 million participants conducted by the American Cancer Society found that the best long-term survival rates were found among those who slept 7 hours a night (6). A 15% increased mortality risk was found among those that reported sleeping more than 8.5 hours and those that reported less than 4.5 hours of sleep a night.

Mechanisms behind short sleep duration and mortality risk

There are a few reasons why short sleep duration may increase the risk of mortality. Finding the link between short sleep duration and increased mortality risk may be more difficult than finding the association between long sleep and disease risk, as those who do not sleep enough represent many different types of people. Some, many, do not have enough time to sleep 7-8 hours a night. Some have insomnia. Some, like shift workers, work all night and can only sleep a few hours during the day. The point is that those who sleep long usually do so by choice, while those who do not sleep enough may require more sleep but are not able to sleep longer for one reason or another.

The mechanisms behind short sleep duration and increased mortality risk likely involve the metabolic and endocrine systems. Studies that have forced subjects to only sleep a few hours a night in a lab have found marked changes in the endocrine system. Short sleep may negatively affect insulin sensitivity and increase levels of proinflammatory cytokines and low-grade inflammation, which can all lead to diabetes (7). Sleep deprivation may negatively alter the hunger and satiety hormones ghrelin and leptin, leading to increased hunger and overeating. Although not supported by research, there is a theory that sleep deprivation leads to a decreased metabolism and less physical activity.

Remember, these short-term studies may not represent the actual mechanism that causes the increased mortality risk seen over decades, not just a few nights of poor sleep in a lab.

Mechanisms behind long sleep duration and mortality risk

There are a few theories about why long sleep duration would cause an increase in mortality risk. Researchers have considered that sleep apnea, when subjects stop breathing while sleeping, may cause them to feel less rested and sleep longer to make up for the broken sleep. Although this sounds plausible, studies thus far have not found an association between sleep apnea and an increased risk of mortality.

Researchers have also considered that depression may cause people to sleep longer and be an underlying cause of poor health, as depression can lead to insomnia, reduced physical activity, and poor eating habits (8). Once again, this sounds plausible, but research has not supported this theory.

Suggested possible reasons for increased mortality may be: longer sleep is associated with higher rates of sleep fragmentation, which has been associated with poor health. Lethargy caused by sleeping excessively could lower our resistance to stress and disease. Our extended period of time in the dark could lead to a disruption of our photoperiod, which has been associated with an increased risk of death in other species. There may also be an underlying reason for the increased mortality risk that we have not examined yet. Prospective studies would greatly enhance our ability to find the links between long sleep duration and increased mortality risk.

Ideal sleep duration and ways to improve sleep quality

Almost every study comparing sleep duration and mortality risk has found that 7-8 hours of sleep a night is ideal. Sleeping more than 8 hours or less than 7 hours seems to similarly increase the risk of all-cause mortality. Although not discussed, the quality of sleep is also important. You can improve the quality of your sleep by using blue light-blocking sunglasses at night, getting room-darkening shades, exercising regularly, only using the bed for sleeping, and getting up and doing something (not using the phone or TV) for a little while if you cannot fall asleep after 20–30 minutes.

Sources

- Luyster, F. S., Strollo, P. J., Zee, P. C., & Walsh, J. K. (2012). Sleep: a health imperative. Sleep, 35(6), 727-734.

- Fiorino, A. S. (1996). Sleep, genes and death: fatal familial insomnia. Brain research reviews, 22(3), 258-264.

- Ferrie, J. E., Shipley, M. J., Cappuccio, F. P., Brunner, E., Miller, M. A., Kumari, M., & Marmot, M. G. (2007). A prospective study of change in sleep duration: associations with mortality in the Whitehall II cohort. Sleep, 30(12), 1659-1666.

- Patel, S. R., Ayas, N. T., Malhotra, M. R., White, D. P., Schernhammer, E. S., Speizer, F. E., … & Hu, F. B. (2004). A prospective study of sleep duration and mortality risk in women. Sleep, 27(3), 440-444.

- Wingard, D. L., & Berkman, L. F. (1983). Mortality risk associated with sleeping patterns among adults. Sleep, 6(2), 102-107.

- Kripke, D. F., Garfinkel, L., Wingard, D. L., Klauber, M. R., & Marler, M. R. (2002). Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Archives of general psychiatry, 59(2), 131-136.

- Knutson, K. L., Spiegel, K., Penev, P., & Van Cauter, E. (2007). The metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Sleep medicine reviews, 11(3), 163-178.

- Youngstedt, S. D., & Kripke, D. F. (2004). Long sleep and mortality: rationale for sleep restriction. Sleep medicine reviews, 8(3), 159-174.